February 1st, 2019

Last year, Zero Invasive Predators Ltd (ZIP) began developing and testing two methods to mitigate potential risks to kea (Nestor notabilis) from a proposed aerial 1080 operation to remove predators from the Perth River valley, South Westland. The two methods are to:

apply non-toxic bait laced with bird repellent to deter kea from eating the toxic bait; and

provide fresh tahr carcasses as a more attractive, preferred, food source.

This Finding, and the accompanying Technical Report, outlines a trial we began in November 2018, in which we investigated whether a repellent, anthraquinone, could be used to ‘teach’ kea to avoid consuming cereal baits.

Anthraquinone is classified as a ‘secondary’ repellent because the compound itself is not detectable in baits, but must be consumed in order to create aversion. The repellent creates a short-lived effect, whereby birds show mild signs of gut discomfort, including gagging behaviour, and sometimes vomiting, after consuming it.

This trial sought to determine whether kea would learn, through repeated exposure to anthraquinone-laced cereal baits, to associate these symptoms with cereal bait, and as a result avoid cereal bait during subsequent exposures – even when baits did not contain anthraquinone.

What did we do?

This trial was designed and carried out with ongoing advice from kea experts at the Department of Conservation (DOC) and University of Auckland.

The trial involved 11 kea, and was carried out in the captive kea enclosure at Willowbank Wildlife Reserve (Canterbury). The enclosure is a large outdoor aviary designed as much as possible to simulate the natural environment of kea.

We used two different cereal baits: Wanganui #7 with a ‘double orange’ lure, and RS5 with a ‘double cinnamon’ lure; these baits taste and smell like orange and cinnamon respectively. Both of these baits will be used in the Perth River valley predator removal operation.

Some of the bait was used in its standard form, i.e. with no repellent. Some was laced with anthraquinone at a concentration of 2.7% by weight (higher concentrations of anthraquinone resulted in darker coloured baits which had a crumblier texture). This concentration was higher than had been tested before with captive birds (e.g. Orr-Walker et al 2012, and Reardon 2014).

The bait manufacturer, Orillion, worked hard to successfully ensure that the standard non-repellent baits and the baits laced with anthraquinone were consistent in texture and shape. Both types of bait were dyed green to replicate the appearance of toxic baits.

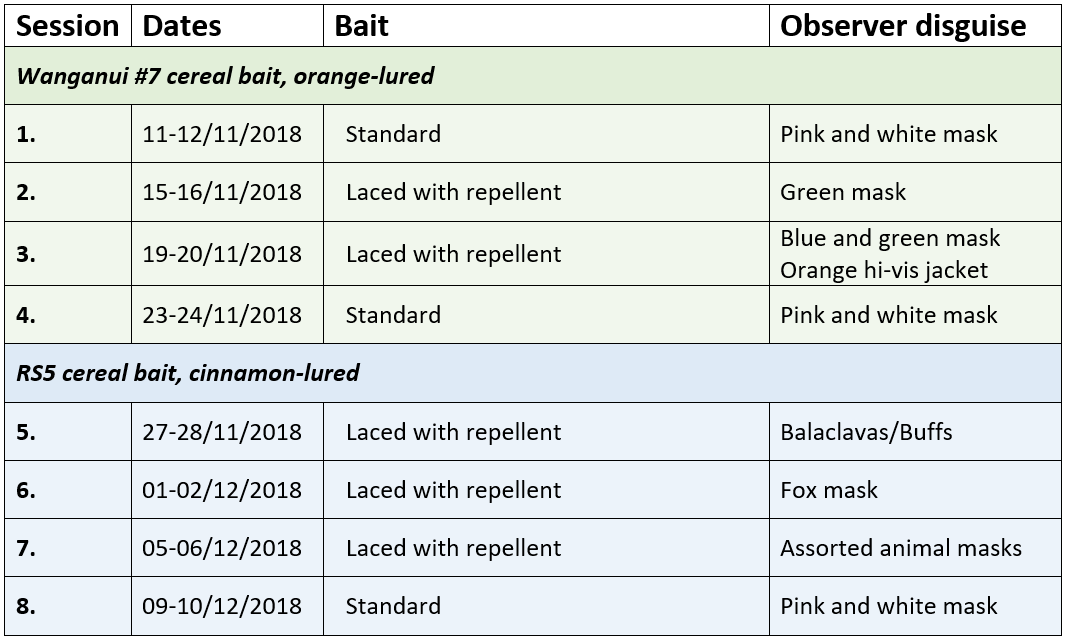

Kea were hand-fed by a team of 4-5 observers, for a total of eight sessions - i.e. four sessions using Wanganui #7 bait, and four using RS5 bait. For Wanganui #7 bait, the first session used standard (non-repellent) bait, followed by two sessions of bait laced with repellent, and finally one session of standard bait. The RS5 bait exposure sequence was three sessions of bait laced with repellent, and a final session using standard bait. Each session was carried out over two days, and comprised one period each day during which kea were hand-fed with the baits for approximately three hours. Between each session the kea had two days eating their normal diet.

During the trial design, kea behavioural experts at the University of Auckland told us that the behaviour of kea in trials can sometimes be influenced by the physical appearances of individual researchers. The experts advised us to try to ensure that the kea behaviours we observed were attributed to the bait itself – not the appearance of the researcher presenting the bait. To this end, the observers wore face masks and, on one occasion, a hi-vis jacket to disguise their appearance. Different masks were used for each session, except for when presenting standard bait (in which case, the same mask was worn).

Observers were located throughout the enclosure to reduce competition for individual baits, and moved around as required to ensure all birds would be exposed to the bait. Each observer presented a single bait at a time, and recorded whether the bait was consumed and, if so, the quantity and start and finish times of that consumption. After a kea had either consumed a bait or discarded it into an area of the enclosure from which the bird was unable to retrieve it, we repeated the process for up to three hours, to maximise the opportunity for all birds to encounter and consume bait.

We presented birds with baits as follows:

What did we observe?

10 out of the 11 captive kea readily consumed bait during Session 1. This level of consumption is likely to be higher than what would be expected in the wild. That’s because: (i) the Willowbank environment has fewer stimuli compared to the natural habitat of kea, and the captive birds are therefore more likely to be drawn to ‘novel’ items of interest than wild kea; and (ii) the trial involved observers actively presenting the birds with multiple opportunities to consume the baits, which does not happen in their natural habitat.

The same 10 out of the 11 birds continued to consume bait on days 1 and 2 of Session 2, i.e. the first session involving bait laced with repellent. However, during the course of each day, most individuals demonstrated behaviours associated with consumption of the repellent, i.e. fluffed feathers, gripping stomach with their feet, a gaping beak, beak wiping, head shaking, gagging, vomiting, and/or inactivity. The symptoms experienced by the birds due to their consumption of anthraquinone appear to have been very short-lived, and all birds returned to normal activity within 30 minutes of ingesting the repellent.

No birds consumed repellent bait during Session 3.

Only one bird consumed a portion of a bait during day 2 of Session 4.

There was a small increase in consumption during Session 5, when the bait type was changed to the cinnamon-lured RS5, which can likely be attributed to the very different smell, and taste, of the bait. During this session, birds were observed actively sniffing and tasting baits before either consuming or discarding them.

Consumption again diminished to near-zero during feeding Sessions 6-8.

The results are shown on the following graph. The different coloured bars represent the 11 individual birds.

Over the course of the trial, Willowbank staff reported that birds behaved and fed normally outside of the trial sessions.

What does this mean for the Perth River valley predator removal operation?

The results of these trials indicate that for any wild kea predisposed to eating bait, the risk to kea of the proposed aerial 1080 operation in the Perth River valley could be mitigated to some degree by training those kea to avoid eating cereal baits.

Consequently, we propose to aerially sow and hand-place anthraquinone-laced bait in kea habitat prior to sowing 1080 during the proposed predator removal operation. The repellent-laced bait will be located above the upper boundary of the area that will be sown with 1080 (approx. 1600-2000m above sea level) to exclude possums and rats from exposure to this bait (as they would subsequently be repelled from eating toxic baits too).

We also propose to use tahr carcasses to draw kea to sites where anthraquinone baits are present, to increase the likelihood they will be exposed to the repellent. Tahr are known to be a highly attractive food source for kea in the Perth River Valley and surrounding area, and our recent trials have provided further evidence to support this approach. We will publish our Findings from that work in the near future.

Want to learn more?

Check out the technical report.

Acknowledgements

This trial would not have been possible without the help of many people from Willowbank Wildlife Reserve, Auckland University, the Department of Conservation, Orillion, Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research, Lincoln University and the Kea Conservation Trust, as well as our own ZIP colleagues (a fuller list of contributors is in the technical report). Thank you all for your help.

References

Orr-Walker T, Adams NJ, Roberts LG, Kemp JR and Spurr EB 2012. Effectiveness of the bird repellents anthraquinone and d-pulegone on an endemic New Zealand parrot, the kea (Nestor notabilis). Applied Animal Behaviour Science 137(1): 80-85.

Reardon J July 2014. Kea repellent development report. Unpublished report to Department of Conservation, 20 p.